1.3. Homeostasis

Understanding Homeostasis

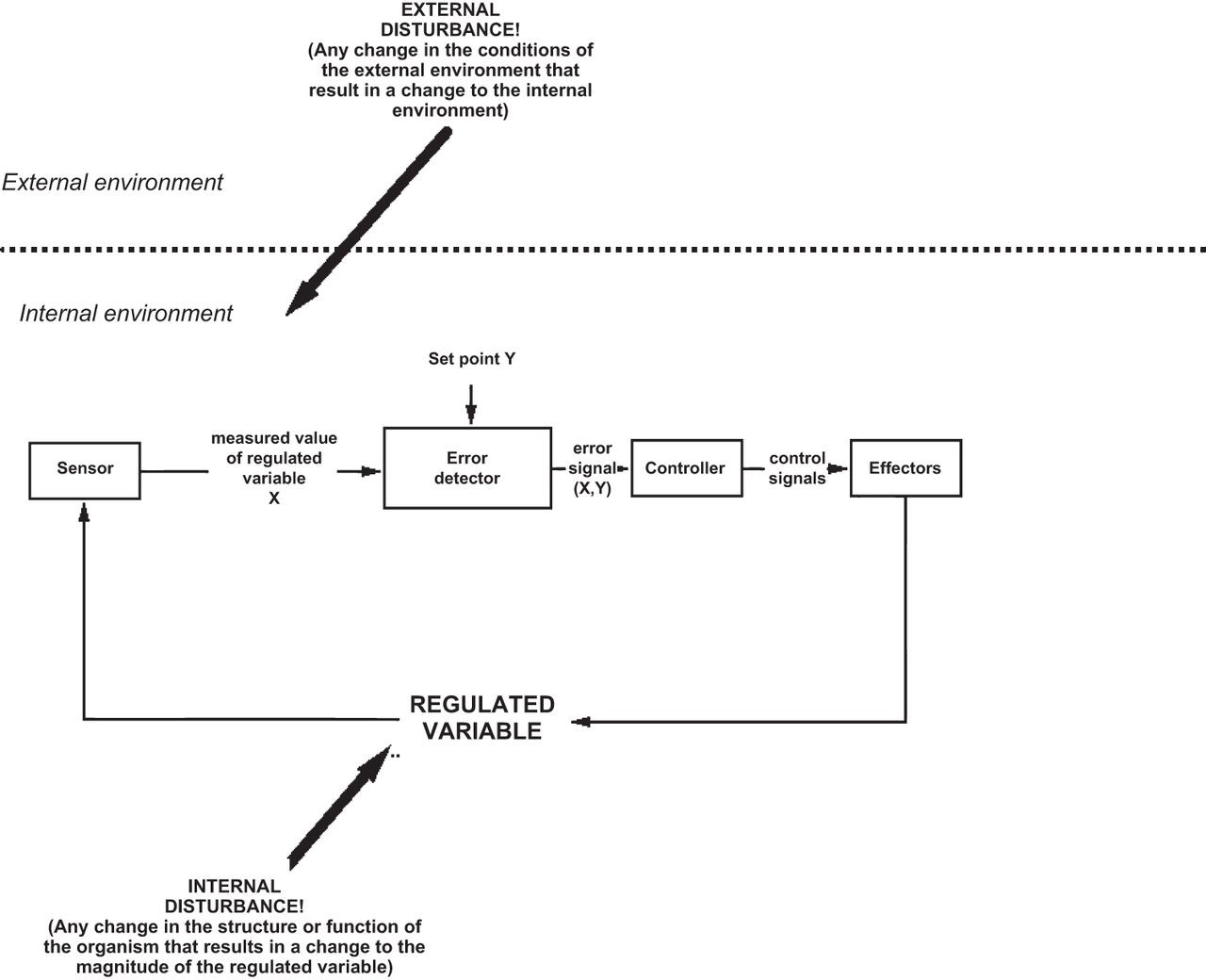

To function properly, the human body must maintain a stable internal environment. This process—called homeostasis—involves constantly monitoring internal conditions and responding to changes. While some parameters fluctuate within wide limits, others (like body temperature and blood pressure) are tightly regulated around a set point, the ideal value.

Specialized receptors detect deviations from the set point and send signals to control centers, often located in the brain. These control centers evaluate the input and activate effectors (e.g., glands or muscles) to counteract the change—usually through a process called negative feedback.

Negative Feedback

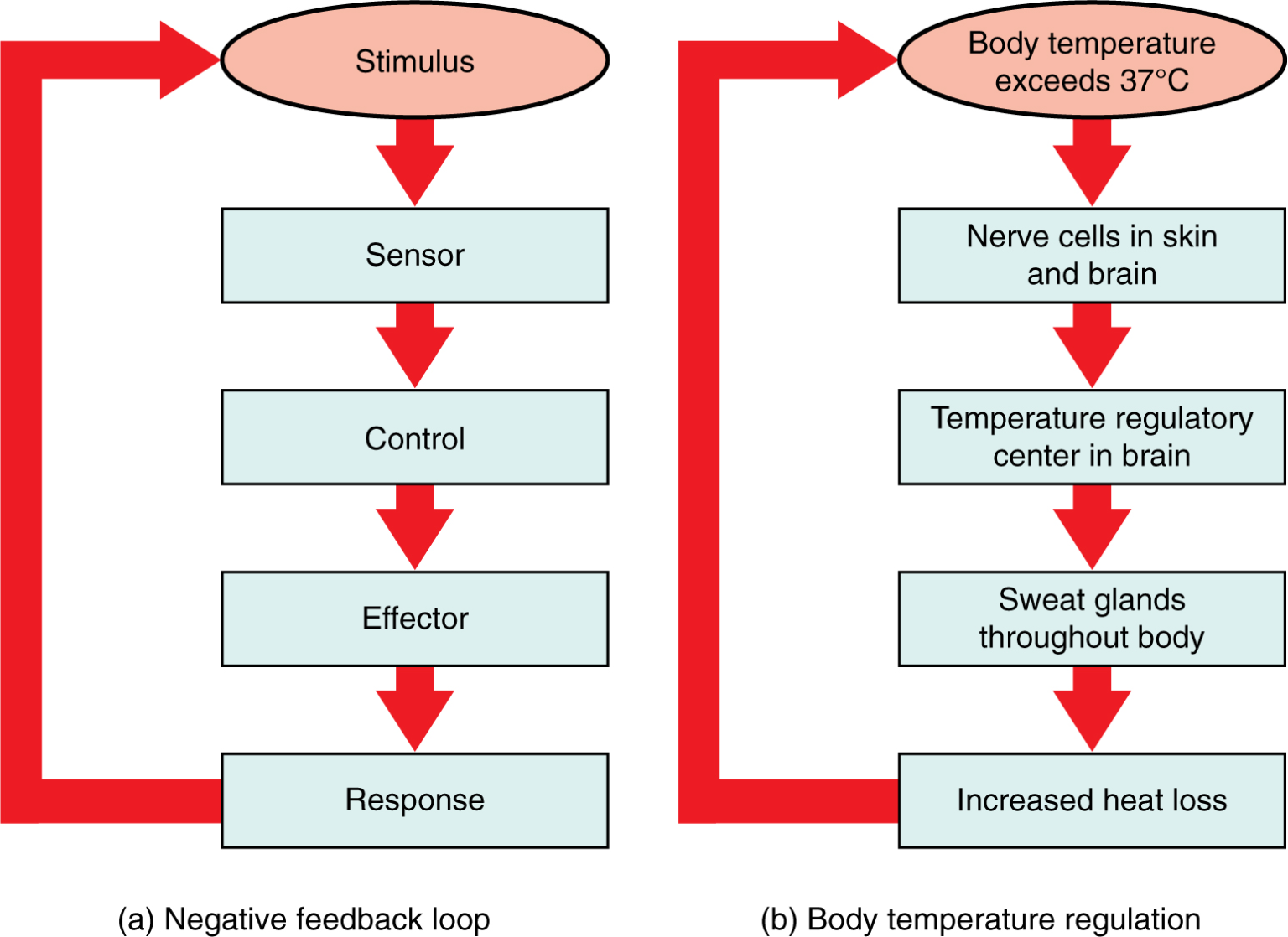

Negative feedback mechanisms are central to homeostasis. They work by reversing deviations from a set point. A typical negative feedback loop includes:

- Sensor: Detects the change

- Control Center: Processes the information and compares it to normal values

- Effector: Executes a response to restore balance

Example – Blood Glucose Regulation: When blood sugar rises, pancreatic beta cells release insulin, prompting the body’s tissues to absorb glucose. As levels normalize, insulin secretion is reduced—restoring homeostasis.

Example – Temperature Control: High body temperature activates the hypothalamus to initiate responses such as:

- Dilation of skin blood vessels (to release heat)

- Increased sweat production

- Increased breathing depth

Positive Feedback

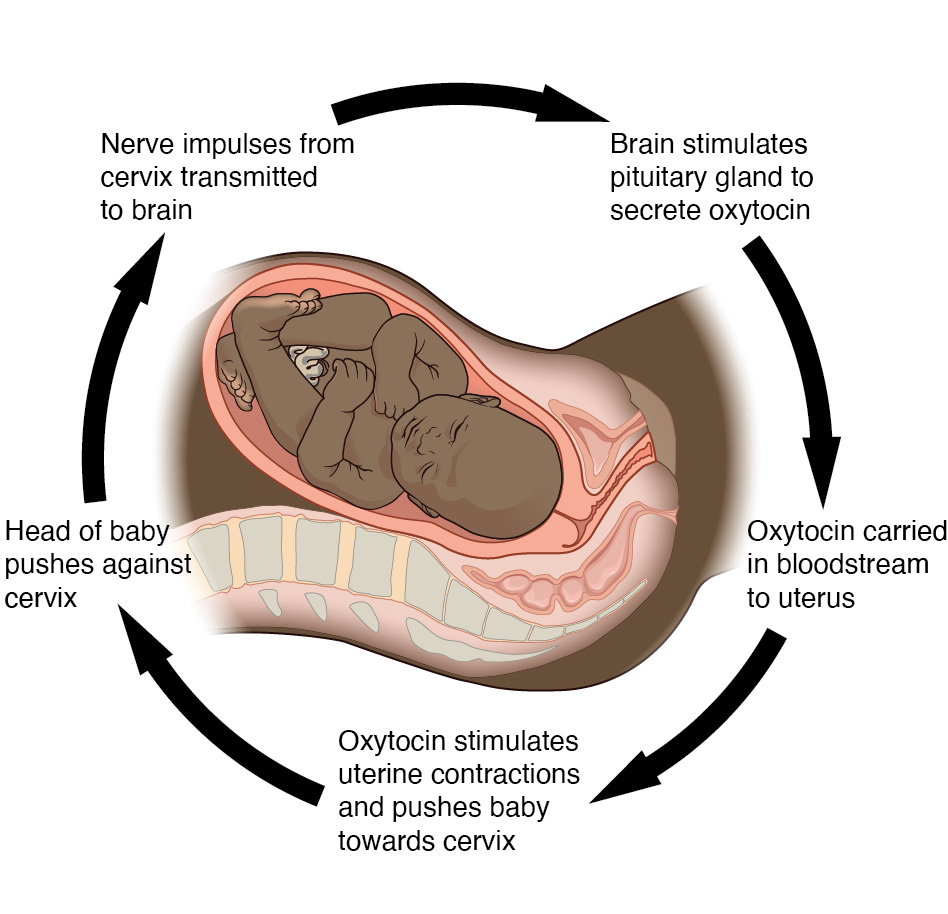

Positive feedback intensifies a change rather than reversing it. Though less common, it plays a key role in processes with clear endpoints.

Example – Childbirth: Stretching of the cervix triggers the release of oxytocin, which enhances uterine contractions. These contractions further stretch the cervix, amplifying the response until birth occurs, at which point the loop ends.

Example – Blood Clotting: When a blood vessel is injured, chemical signals promote clot formation. Each step activates more clotting factors until the bleeding stops.